Why Product Management Matters

I remember sitting in a conference room years ago, surrounded by product managers, developers, and designers. We were three sprints into a project and nobody could agree on what “done” actually meant. The requirements document was 47 pages long. The developers were building features that nobody asked for. The designers were frustrated. And the client? They just wanted something that solved their problem.

That project taught me something that I carry with me to this day: the quality of your input determines the quality of your output. Back then, we were talking about requirements documents and user stories. Today, we might be talking about prompts and AI-generated code. But the fundamental truth remains the same whether you are writing every line by hand or letting AI handle the typing.

Here is the thing: tools change, but the hard problem stays the same. You can mass produce code faster than ever, but that does not help if you are building the wrong thing. You cannot interview your users with a keyboard shortcut. You cannot synthesize conflicting feedback into a coherent product vision with a CLI command. You cannot decide which problem is worth solving first by asking an LLM.

That is product management. And in a world where writing code is getting easier every year, the ability to define what gets built clearly, precisely, testably, is the skill that matters most.

The Problem Is Not New, But It Is Getting Louder

Y Combinator reported that 25% of startups in their Winter 2025 batch had codebases that were 95% AI-generated. That statistic makes a lot of people nervous about the future of software development. But here is what it actually reveals: the bottleneck was never typing speed.

The developers getting the best results, whether they are using AI tools or not, are the ones who actually understand what they are trying to build before they start.

In May 2025, a Swedish vibe coding app called Lovable was found to have security vulnerabilities in 170 out of 1,645 web applications it helped create. The code looked fine, it ran fine, but it was fundamentally broken because nobody stopped to ask the right questions first.

That is not an AI problem. That is a requirements problem. And requirements problems have been shipping broken software since long before anyone heard of large language models.

Enter Design Thinking (Yes, the Sticky Note People)

I know what you are thinking. “Design thinking? That is for UX designers and people who like whiteboards.”

The LUMA Institute has been teaching human-centered design for years. Their framework breaks down into three core skills: Looking, Understanding, and Making (A for aligning or adapting depending on who you ask). It is not complicated, but it is powerful, and it is exactly what most development processes are missing.

Looking is about observing human experience. Who are your users? What are they actually trying to accomplish? What frustrates them?

Understanding is about analyzing challenges and opportunities. What patterns emerge? What assumptions are you making?

Making is about envisioning future possibilities. What does success look like? How will you know when you get there?

Sound familiar? It should. These are the exact questions you need to answer before you write a single line of code, regardless of how that code gets written.

From Observations to User Stories: The Methods That Actually Work

Here is where design thinking gets practical. LUMA does not just give you philosophy. It gives you a framework, specific methods for moving from “I have a bunch of observations” to “I know exactly what to build.” Here are the modules I use most often, with some examples.

Rose, Thorn, Bud: Sorting the Signal from the Noise

When you are in the Looking phase, you collect a lot of information. User interviews, support tickets, analytics data, competitor analysis. It is overwhelming. Rose, Thorn, Bud helps you make sense of it.

The method is simple. Take all your observations and sort them into three categories:

Roses are things that are working well. These are the features users love, the workflows that feel smooth, the moments of delight. Do not skip this category. Understanding what works is just as important as understanding what does not.

Thorns are pain points. These are the frustrations, the workarounds, the things that make users curse under their breath. Every thorn is a potential user story waiting to happen.

Buds are opportunities. These are the “what if” moments. The features users wish existed. The adjacent problems you could solve. Buds often become your most innovative features.

Here is what this looks like in practice. Say you are building an expense tracking app for small business owners. After interviewing ten users, you might end up with:

Roses:

- Users love being able to photograph receipts on their phone

- The monthly summary report saves them hours at tax time

- Integration with their bank account means less manual entry

Thorns:

- Categorizing expenses is tedious and error-prone

- No way to split a single receipt across multiple expense categories

- Forgot to log expenses until a week later, then could not remember the details

Buds:

- Several users mentioned wishing they could see spending trends over time

- One user manually tracks which expenses are tax-deductible versus not

- A few users share expense responsibilities with a business partner

Now you have raw material for user stories. But which ones should you build first?

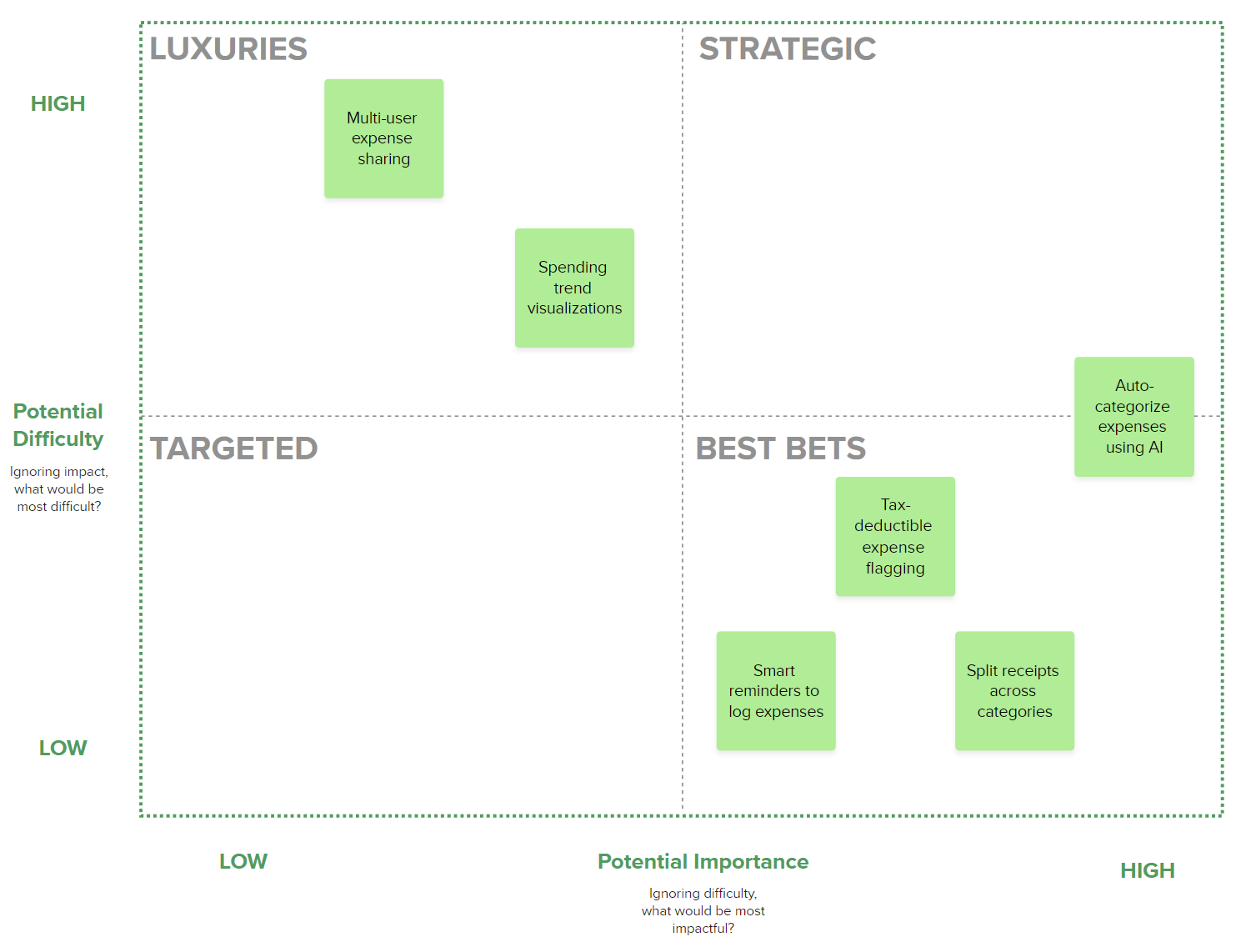

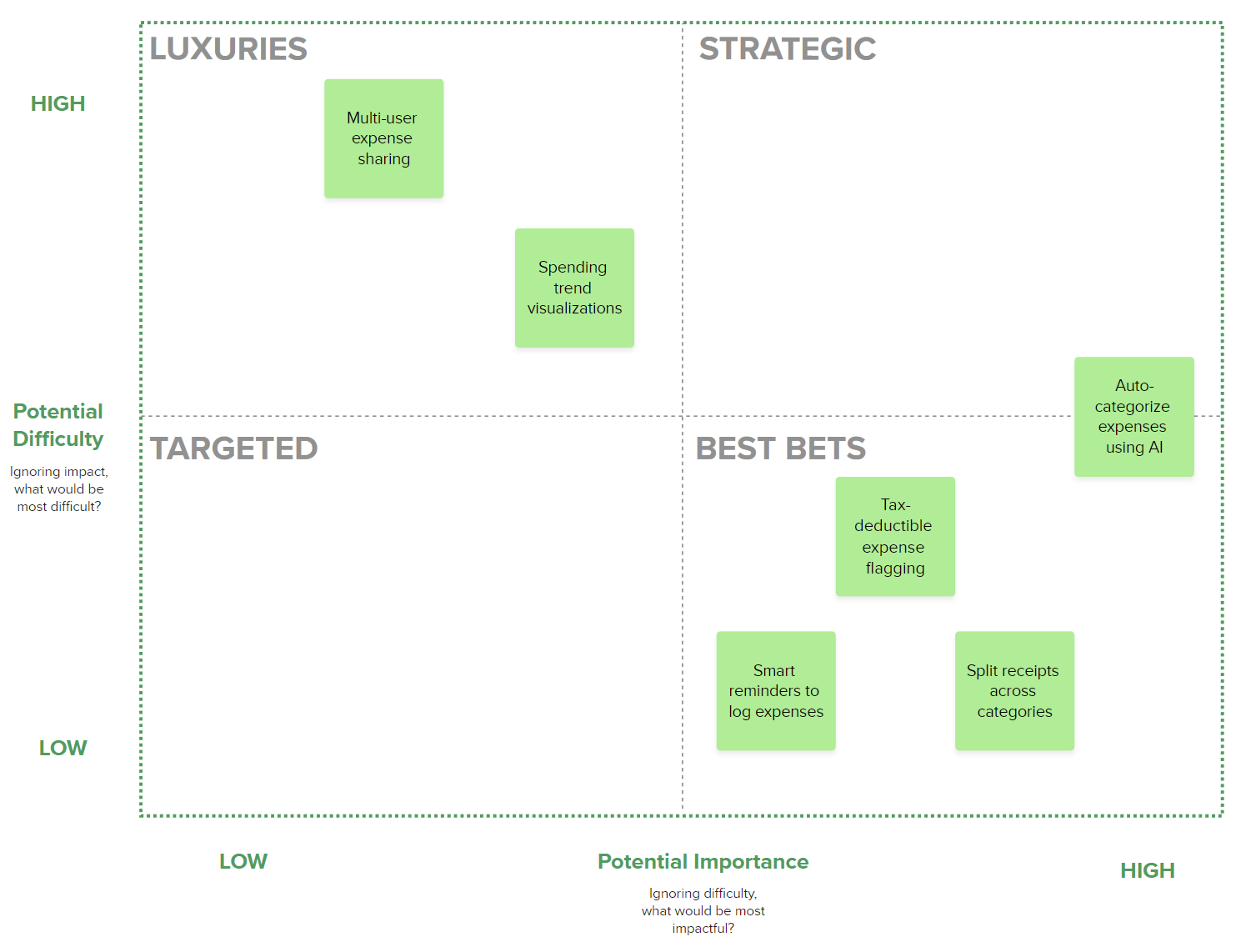

Importance/Difficulty Matrix: Picking Your Battles

Not all user stories are created equal. Some will take months to build and barely move the needle. Others can be shipped in a week and transform the user experience. The Importance/Difficulty Matrix helps you see the difference.

Draw a 2x2 grid. The vertical axis is Difficulty (how hard is this to implement?). The horizontal axis is Importance (how much does this matter to users?). Start with the importance and do your best to ensure that each item is in its own spot, no overlapping (if possible). Once you have the importance you can start to move each item up towards the proper difficulty level. This exercise helps you identify easy wins, important considerations for difficult initiatives, etc.

Plot each potential feature or user story on the grid.

High Importance, Low Difficulty (bottom right): These are your quick wins. Do these first. They deliver value fast and build momentum.

High Importance, High Difficulty (top right): These are your major projects. Important but need significant investment. Plan carefully.

Low Importance, Low Difficulty (bottom left): Fill-in work. Nice to have but not urgent. Good for junior developers or slow weeks.

Low Importance, High Difficulty (top left): Time sinks. Avoid these. They burn resources without delivering proportional value.

Taking our expense app thorns and buds:

| Feature |

Importance |

Difficulty |

Quadrant |

| Auto-categorize expenses using AI |

High |

Medium |

Quick Win |

| Split receipts across categories |

High |

Low |

Quick Win |

| Spending trend visualizations |

Medium |

Medium |

Major Project |

| Tax-deductible expense flagging |

High |

Low |

Quick Win |

| Multi-user expense sharing |

Medium |

High |

Time Sink? |

| Smart reminders to log expenses |

High |

Low |

Quick Win |

Look at that. Four quick wins jumped out immediately. Those become your first sprint. The multi-user sharing might seem cool, but the effort-to-value ratio is terrible right now. Maybe later, once you have nailed the core experience.

Affinity Clustering: Finding the Patterns You Missed

Sometimes your observations do not fit neatly into categories. You have sticky notes everywhere and no clear picture. Affinity Clustering helps you find the hidden structure.

The process works like this:

- Write each observation, quote, or insight on its own sticky note (or digital equivalent)

- Start grouping notes that seem related. Do not think too hard. Go with your gut.

- As clusters form, give them names. What theme connects these observations?

- Look at the clusters. Which ones are biggest? Which ones surprise you?

I did this recently with support tickets for a SaaS product. The obvious clusters were what you would expect: billing issues, feature requests, bug reports. But then an unexpected cluster emerged: users trying to do things the product was never designed for. They were using a project management tool to run their entire small business.

That cluster became a product pivot discussion. We never would have seen it if we had just triaged tickets the normal way. This does not mean you always need to pivot, in the end we realized that a proper integration would be more beneficial, but that integration became a priority.

For our expense app, Affinity Clustering might reveal that three seemingly unrelated thorns are actually the same underlying problem:

- “Categorizing expenses is tedious”

- “Forgot to log expenses until a week later”

- “Can’t remember what this $47.32 charge was for”

Take the time to really dig into the root cause and why it matters when you try to title the cluster. Users lose the context needed to accurately log expenses as time passes.

Cluster name: “Context Decay: delays in reporting expenses lead to poor reporting, gaps in actual finances, and frustration from those filing/processing the expenses” vs “Context Decay”.

Now instead of three separate features, you have one user story that addresses the root cause:

As a small business owner, I want to log expenses immediately after purchase with minimal friction so that I capture accurate details before I forget them.

That is a much better foundation than “make categorizing easier,” whether you are writing the code yourself or handing it off to an AI tool.

The User Story: Clarity That Scales

User stories have been around since the early days of Agile. The format is simple:

As a [type of user], I want [some goal] so that [some reason].

For example: “As a busy parent, I want to save my grocery list so that I do not have to remember everything at the store.”

But the magic is not in the format. It is in what the format forces you to do. You have to think about who the user is. You have to articulate what they actually want. And most importantly, you have to explain why it matters.

This is where the INVEST criteria comes in. Good user stories should be:

- Independent: Not tangled up with other stories

- Negotiable: Open to conversation, not set in stone

- Valuable: Actually useful to someone

- Estimable: Clear enough to estimate the work

- Small: Completable in a reasonable timeframe

- Testable: You can verify when it is done

These criteria matter whether you are handing the story to a junior developer, a senior architect, or an AI coding assistant. Vague input produces vague output, while clear input produces clear output. The tool does not change the equation.

Acceptance Criteria: The Bridge Between “What” and “Done”

This is where things get really interesting. In Agile, every user story comes with acceptance criteria. These are the specific conditions that must be met for the story to be considered complete. The most common format uses Given/When/Then:

Given [some context]

When [some action is taken]

Then [some outcome is expected]

For example:

- Given a user is logged in

- When they click “Save List”

- Then their grocery items should persist across sessions

This is not just documentation, this is a testing specification. And whether you are writing tests by hand, using TDD, or letting AI generate your test suite, acceptance criteria tell you what “correct” actually means.

Putting It All Together: From Sticky Notes to Shipping Code

Let me walk you through the full workflow using our expense app example.

Step 1: Looking (Rose, Thorn, Bud)

You interview users and observe their behavior. You collect observations and sort them:

- Rose: “I love that I can just snap a photo of the receipt”

- Thorn: “I always forget to log my expenses until it’s too late”

- Thorn: “The categories never match how I actually think about spending”

- Bud: “Wish it could just tell me what category something should be”

Step 2: Understanding (Affinity Clustering)

You notice the thorns cluster around a theme: users lose context over time. The bud suggests users want intelligence, not just data entry.

Cluster: Context Decay and Cognitive Load: delays in reporting expenses lead to poor reporting, gaps in actual finances, and frustration from those filing/processing the expenses

The real problem is not the interface. It is that expense tracking requires too much mental effort at the wrong time.

Step 3: Prioritizing (Importance/Difficulty Matrix)

You brainstorm potential solutions and plot them:

- AI-powered auto-categorization: High importance, Medium difficulty → Build it

- Push notification reminders: High importance, Low difficulty → Build it now

- Voice memo for expense context: Medium importance, Low difficulty → Quick win

- Full accounting system integration: Medium importance, High difficulty → Later

Step 4: Writing User Stories

Based on your analysis, you write:

As a small business owner who makes frequent purchases, I want expenses to be automatically categorized based on the merchant and amount so that I spend less mental energy on bookkeeping.

Step 5: Defining Acceptance Criteria

Given a user photographs a receipt from a merchant they have used before

When the app processes the image

Then it should auto-suggest the same category used previously with 90%+ confidence

Given a user photographs a receipt from a new merchant

When the app processes the image

Then it should suggest a category based on merchant type and purchase amount

And allow the user to confirm or change the category with one tap

Given a user overrides an auto-suggested category

When they encounter the same merchant again

Then the system should learn from the correction and suggest the new category

Step 6: Building

At this point, you have everything you need to build the feature correctly. If you are coding by hand, you have clear requirements and testable criteria that you can put into a ticketing system (e.g. Jira, Trello, etc). If you are using AI tools, your prompt practically writes itself (but you should still use a ticketing system and create a feature branch based on that ticket, but I digress):

You are building an intelligent expense categorization feature. Here is the context:

User Story: As a small business owner who makes frequent purchases, I want

expenses to be automatically categorized based on the merchant and amount

so that I spend less mental energy on bookkeeping.

The core insight from user research: Users lose context over time and find

manual categorization tedious. They want the system to learn their preferences.

Acceptance Criteria:

1. Given a user photographs a receipt from a merchant they have used before

When the app processes the image

Then it should auto-suggest the same category used previously with 90%+ confidence

2. Given a user photographs a receipt from a new merchant

When the app processes the image

Then it should suggest a category based on merchant type and purchase amount

And allow the user to confirm or change the category with one tap

3. Given a user overrides an auto-suggested category

When they encounter the same merchant again

Then the system should learn from the correction and suggest the new category

Tech stack: React Native, TypeScript, Supabase, OpenAI API for OCR

Design constraints: Must work offline with sync, categorization UI must be

completable in under 3 seconds

Please implement this feature including:

- Data model for storing merchant-category associations and user corrections

- Service layer for category prediction logic

- React Native components for the categorization UI

- Unit tests that verify each acceptance criterion

Compare that to “build me an expense categorization feature.” The difference is not subtle, and it does not matter whether a human or an AI is on the receiving end.

QA: Testing What Actually Matters

Here is something that keeps me up at night: AI can generate tests for the code it writes. Sounds great, right? The problem is that AI-generated tests often only cover the happy path. They test what the code does, not what it should do.

This is why acceptance criteria matter so much. They are not just documentation. They are your test specification. When you write:

Given a user with no internet connection

When they try to save a task

Then the task should be queued locally and synced when connection is restored

You have just written a test case! A test case that reflects real user needs that you discovered through the Looking and Understanding phases of design thinking.

The teams that are shipping quality software are the ones who:

- Start with design thinking to understand the actual problem

- Use methods like Rose/Thorn/Bud, Affinity Clustering, and Importance/Difficulty to synthesize insights

- Write user stories with clear acceptance criteria

- Use those criteria to verify the implementation, however it was built

- Review the output against the original user story, not just “does it run”

Metrics That Actually Mean Something

When you have clear user stories and acceptance criteria, measuring success becomes almost trivial. Did we meet the acceptance criteria? Yes or no. Does the feature solve the problem described in the user story? Yes or no.

Compare this to the alternative: “We shipped 47 features this quarter.” Great. Did any of them matter?

Some metrics that actually work:

- Acceptance Criteria Pass Rate: What percentage of your acceptance criteria are met on first deployment?

- User Story Completion: Not “did we build it” but “did we solve the problem”

- Iteration Count: How many times did you have to go back and refine? (Fewer is better and cheaper, and it usually means your original specification was clearer)

- Post-Deploy Defects by Criteria Type: Where are the bugs? In the functionality? The edge cases? The performance? This tells you where your acceptance criteria need more rigor.

A Word of Caution

I am not saying design thinking and user stories will solve all your development problems. Complex systems still have complex bugs. Edge cases still slip through. Requirements still change mid-project.

But here is the thing: those problems are way easier to catch when you know what you were trying to build in the first place. When you have clear acceptance criteria, you can actually test whether the implementation is correct. When you have done the design thinking work, you can recognize when you are solving the wrong problem.

The developers I know who are thriving are not the ones who type the fastest or use the newest tools. They are the ones who got better at thinking clearly about what they are building.

Getting Started

If you want to try this approach, here is what I would suggest:

-

Start with Rose/Thorn/Bud: Before you decide what to build, understand the landscape. Talk to users, review support tickets, observe behavior. Sort everything into roses (working well), thorns (pain points), and buds (opportunities). Do not skip this step. You cannot write good user stories about problems you do not understand.

-

Cluster your observations: Spread out your roses, thorns, and buds. Group the ones that seem related. Name the clusters. This is where you discover that five seemingly unrelated complaints are actually one underlying problem. These clusters become the foundation for your user stories.

-

Prioritize with Importance/Difficulty: Now you have clusters of insights. Plot them on the matrix. Which problems are high importance and low difficulty? Those are your starting points. The matrix does not tell you what features to build. It tells you which problems to solve first.

-

Let user stories emerge: For each prioritized problem, write a user story. The story should flow naturally from your research. “As a [user you interviewed], I want [solution to the thorn you identified] so that [benefit that addresses the underlying cluster].” If you did the design thinking work, the user stories should almost write themselves.

-

Define acceptance criteria: For each user story, write Given/When/Then statements that describe what success looks like. These come directly from your observations. What did users say they needed? What would make the thorn disappear?

-

Store the context in your codebase: Create a directory (something like /docs/stories or /.context) and add it to your .gitignore. Save your user stories and acceptance criteria as markdown or text files. When you are working with AI coding tools like Claude Code or Cursor, they can reference these files directly. This means you do not have to paste the same context into every prompt. The AI has access to the full picture: the user story, the acceptance criteria, the reasoning behind your decisions. Update these files as your understanding evolves. Even if you are not using AI tools, having this documentation in your repo keeps everyone aligned.

-

Build with confidence: With your context in place, you know exactly what you are building and how to verify it. Whether you are writing code by hand, pair programming, or using AI assistance, the foundation is solid.

Notice what is missing from this list: “Pick a feature.” You do not start by deciding what to build, you start by understanding what problems exist. The features reveal themselves through the process.

The Bottom Line

The way we write code is changing. AI tools are getting better every month. But the teams that will thrive are not the ones who learn to use the newest IDE or write the fanciest prompts. They are the ones who learn to think clearly about what they are building before they start.

This is product management. Whether your title says “PM” or not, the moment you start defining problems, prioritizing solutions, and writing acceptance criteria, you are doing product work. Design thinking gives you the methods. User stories give you the format. Acceptance criteria give you the tests. Together, they give you the ability to build software that actually solves problems.

The irony is that as building gets easier, the human skills of understanding users, synthesizing insights, and defining success become more valuable, not less. The sticky notes on the whiteboard are not obsolete. They are now the most important part of the process.

The revolution is not in the tools, it is in what you feed them, and feeding them well is a product management problem.

Vatché

Tinker, Thinker, AI Builder. Writing helps me formulate my thoughts and opinions on various topics. This blog's focus is AI and emerging tech, but may stray from time to time into philosophy and ethics.